Chris Lemoh, an Australian of African and European descent, wrote a response to my essay Are there Black people in Australia? Lemoh rejects the description of himself as ‘Black’, saying ‘It’s your label, not mine.’ Pivotal to this rejection is his characterisation of ‘Black’ as a label.

Lemoh begins his essay with a (sound and perfectly orthodox) denunciation of biological racism, and identifies Blackness as ‘political’, not ‘racial’. What is missing from his analysis is a serious engagement with the social dimensions of race and racism. While he notes the occurrence of structural racism – he refers to the use of racialisation ‘to control and damage groups of people’– he does not acknowledge that this is an occurrence. The general phenomenon – the social reality of Blackness in Australia – remains invisible in his essay.

This invisibility is reinforced by the way that Lemoh’s essay skirts about its edges. Lemoh discusses his own experiences, which feature people around him being racist towards various non-whites with the exception of non-Indigenous Blacks. When he acknowledges racialisation he limits it to ‘specific localities arising from specific historical events’: slavery in the Americas, apartheid in South Africa and colonisation in Africa and Australia.

Whatever his intention, Lemoh ends up reproducing the standard Australian perspective on race: that non-Indigenous Black Australians are not subjected to racism, at least not in any significant structural sense, and that we should reject the notion of race as an analytical tool.

Lemoh’s only substantial departure from this standard view seems to be an allowance that race, as well as being a pejorative notion to be used by racists, is also useful as a political tool. He concedes that there are racialised people who have successfully used ‘Black’ as a political label. But, as an African Australian, he does not feel justified in doing so for himself.

This combination of the standard view with a recognition of race-based political activism makes it unsurprising that Lemoh’s essay has attracted praise. What is surprising is that amongst the admirers is Maxine Beneba Clarke– an author whose work gives testimony to the social reality of the racialisation of non-Indigenous Blacks. Clarke writes:

Thank you Chris for such an articulate and eloquent article. I identify as black when I am in the UK (or would in the US), but circumstances in Australia are different. Eg in the States and the UK – even in the Caribbean, there is not a black indigenous population (but Arawak Indians / Native Americans).

This distinction is becoming increasingly important.

Yes, I consider myself an ally. Yes, my skin may be the exact same tone as my indigenous neighbour. No, this is not my land. So: no, I am not going to use a label which may intimate I have equal claim to it / that I bear the same legacy of colonisation. I feel that saying that I am an ‘Australian of Afro-Caribbean descent’ as opposed to a ‘black Australian’ is a very important distinction.

If Clarke is not going to use the label ‘Black’, then how is she to describe certain aspects of non-Indigenous Australian experience?

‘We were the only black children for miles around. If we saw a black person in the street, my mum would run and get their phone number.’

‘Turning up for a job and seeing their faces, because you don’t sound black on the phone.’

May 3, 2014, http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/maxine-beneba-clarke-20140501-37iro.html#ixzz3VSeDpdAQ

‘As a non-Indigenous black Australian, the Beyond Blue advertisements are excruciating to watch. I’ve been there: in that interview room;’

‘Less than a week later the only other black student in the class, a friend of mine, who’s been ill and barely attended tutorials, mentions she was given 18.5 out of 20 for her class participation mark. We both agree on what’s happened.’

‘Black Australian footballer Heritier Lumumba (aka Harry O’Brien), also a star Collingwood player, stepped forward to condemn the words of his club president. “In my opinion race relations in this country is systematically a national disgrace…”’

October 6, 2014, http://rightnow.org.au/writing-cat/no-singular-revelation/

It’s not easy to see how the same meaning could be conveyed using other language, such as reference to place of origin.

Identifying by one’s place of origin, rather than as Black, is problematic for other reasons too. Australians who are not of white British descent are constantly identified by their place of origin – regardless of how remote that ‘origin’ is – while whites of British descent are not. The effect is to single out non-whites and non-British as being from elsewhere and therefore less Australian.

For me, ‘Black’ indicates my lived experience as a racialised person in Australia, not my ‘place of origin’, so the label ‘Australian of such-and-such non-white descent’ is even less appropriate than it might be for a migrant or the child of a migrant such as Clarke.

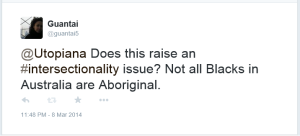

In the conversation that follows Lemoh’s essay, we begin to see glimpses of the reasoning behind objections to African Australians identifying as Black. Far from the stated claim that they are not Black – or not entitled to call themselves Black – the motivation seems to be a desire to avoid ambiguity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Blacks. This is consistent with Lemoh’s characterisation of ‘Black’ as a political label.

But Clarke’s call to avoid ambiguity by having non-Indigenous Blacks not refer to themselves as ‘Black’ in the Australian context makes no more sense than demanding that white women not call themselves ‘women’ for the purpose of supporting Black women’s activism. That ‘Black’ is considered synonymous with ‘Indigenous’ in Australia is only due to the erasure of non-Indigenous Blacks, and is not something that can be defended without their continued erasure.

When Lemoh writes of the marginalisation and erasure of Indigenous Blacks in his childhood history books, he makes no mention of the erasure of non-Indigenous Blacks. He overlooks non-Indigenous Blacks such as John Caesar, the first Australian bushranger; William Blue, the pioneering ferryman of Sydney Harbour; or John Joseph, the first man to stand trial following the iconic Eureka rebellion, whose Blackness was central to the rebels’ legal defence. Their absence is too complete to be noticed.

Clarke’s fear that Indigenous and non-Indigenous Blacks will homogenise – or at least be seen to be homogenous – if we refer to them by the same term is also unfounded. Black Harmony Gathering is an event in which Indigenous and non-Indigenous Blacks are referred to by the singular term ‘Black’ and yet the heterogeneity of their performances couldn’t be more evident.

As I discuss in Are there Black people in Australia? , ambiguity in the use of the term ‘Black’ is an issue. However, it is not an issue to be resolved by the continued censoring and elimination of non-Indigenous Black identity in Australia.

POSTSCRIPT: On 9 November 2017, in the comments below his essay, Chris Lemoh wrote a retraction of the main tenets of his argument.